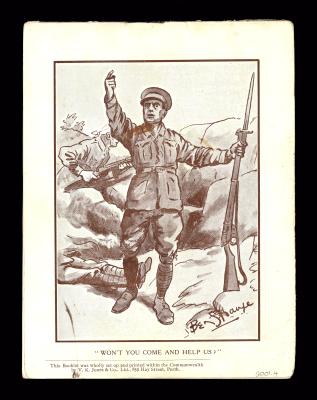

CARTOON - YOUR EYES HAVE TOLD ME SO

1918Scene set in a park. Three old women sitting on a park bench with another woman standing to the left. To the right is a tree and to the right of that is a fifth woman, young. Standing in front of the bench and looking stern is a man in a suit holding his hat in one hand & has his hands on his hips. None of the women are looking at him.

Ben Strange signature bottom left

The cartoon was published in the Western Mail on 22 March 1918 with the caption:

"Your Eyes Have Told Me So."

Mr Lovekin in his evidence before the Select Committee in the new Health Bill:- I have generally noticed that whenever there is anything wrong there is revulsion to the eye.’ In even smaller letters, and in brackets,it is noted that ‘(There is no truth that the Government intends to appoint an expert eye-gazer to patrol parks and reserves in search of suspects).

This 1918 cartoon shows Mr Arthur Lovekin (who at the time was sole owner and editor of the Daily News as well as a candidate for the Legislative Council) looking suspiciously at a demurely dressed young woman whose eyes are downcast as she crochets. Meanwhile Lovekin ignores the more suspect women in the cartoon including a young seductress who stands behind him. She is dressed in figure-hugging clothes and wears high heels, whilst holding a fur stole. Her expression is coy, in contrast to the modest expression of the woman who attracts Lovekin’s gaze. Similarly, three older women of disreputable appearance sit on a park bench, talking with one another. Aged, seated with legs apart, wearing well-worn shoes they are not respectable. Indeed, one seems to be drinking out of a flask - could it be alcohol? Ladies do not lounge in parks in such a way. Despite their appearance they are not of interest to Lovekin. It is possible that the three figures represent some of the key campaigners for and against the new law. Edith Cowan (possibly sitting figure on right) was a strong campaigner for the compulsory reporting of venereal diseases. Bessie Rischbieth (possibly middle sitting figure) campaigned against the laws. Both women were members of the influential women's only Karrakatta Club, Women's Service Guild and were founders of the Children's Protection Society. They along with Dr Roberta Jull and Lady Eleanora James were vocal advocates on women's and children's social and health issues.

The writing beneath the Cartoon says:

‘Mr Lovekin in his evidence before the Select Committee in the new Health Bill:- I have generally noticed that whenever there is anything wrong there is revulsion to the eye.’ In even smaller letters, and in brackets,it is noted that ‘(There is no truth that the Government intends to appoint an expert eye-gazer to patrol parks and reserves in search of suspects).

The cartoon makes fun of Arthur Lovekin’s declaration before the Select Committee into the 1918 amendment to the 1911 Health Act that he can determine whether or not someone was of suspect character, i.e. had a venereal disease, just by looking at them. Whilst his suspicious gaze is drawn to the one respectable looking woman in the image, the 4 other women, all of uncertain character, are of little interest to him.

Historical Analysis

Fierce debate followed the introduction of a bill to alter the Health Act of 1911 with regard to the reporting of venereal disease. This issue had first arisen in 1915, resulting in the 1915 amendment to the Health Act. With WW1 resulting in an increase in the number of cases of venereal disease in WA, a consequence of infected soldiers returning from Britain and Europe, there was interest in WA in reporting and controlling the spread of venereal diseases. The 1915 amendment to the 1911 Health Act made the signed statement of an informant claiming another individual had venereal disease, sufficient evidence to warrant further investigation by the Commissioner of Health. It was then necessary for the accused to provide medical evidence they were not diseased. In a situation where the accused did not produce such a certificate, a warrant could be issued for the accused to be examined by 2 medical practitioners, and the result of this examination sent to the Commissioner in writing.

The 1918 amendment removed the need for a signed statement from an informant. Instead it was enough for the Commissioner to suspect an individual had a venereal disease for that person to be forced to obtain a certificate to the contrary. With no named informant now required, there was concern within the community that anonymous allegations could be made out of malice against virtuous men and women .

Hal Colebatch, the Colonial Secretary in 1918, believed the ‘signed statement [introduced in 1915] had proved a bar to the effective operation of the provision that persons suffering from venereal disease shall compel themselves to treatment. It has been prooved in practice that no woman will sign a statement against a man, and that no man will sign a statement excepting against a common prostitute.’ (West Australian, Saturday 6 April 1918, p.8).

Public meetings were held protesting against the 1918 amendment. On Friday 8 March 1918 Archbishop O’Riley presided over a meeting at St Andrew’s Hall in Pier Street that was attended by ‘a preponderance of women’(West Australian, Saturday 9 March 1918, p.7). Their concern was that the anonymity of the accuser meant a basic precept of British justice was ignored; the right of the accused to know by whom they had been accused. In particular it was feared that innocent young women, who had little legal recourse, could be unjustly targeted by jilted paramours. Whilst the meeting made it clear many people supported the need to report and treat cases of VD, the processes established with the 1915 amendment were seen as more appropriate to this task.

In March 1918 Arthur Lovekin gave evidence before the Select Committee into the amendment to the Health Bill. He declared that having seen hundreds of cases of venereal disease in the Children’s Hospital, and elsewhere, he ‘generally noticed - I do not know what the doctors call it - that whenever there is anything wrong there is revulsion to the eye’. The response of Dr Atkinson, Commissioner of Public Health, was to note that ‘I suppose it is hardly for me to correct any wrong impressions which may have grown up in Mr Lovekin’s mind, but I do not, for instance, think it is always possible to tell a venereal case by simply looking at the patient.’ (West Australian, Monday 11 March 1918, p.8).

The problems posed by soldiers contracting VD whilst on service was common in all countries involved in WW1. In 1931 it was estimated that during WW1, VD caused 416,891 hospital admissions among British and Dominion troops. Roughly 5% of British troops who enlisted were infected at some stage with VD. Some historians believe that the rate of infection was even higher for Australian and Canadian troops as these soldiers were paid more than British troops, encouraging more visits to brothels .

Details

Details

Artist's signature bottom left [Ben Strange]

HIGH

The Ben Strange cartoons are historically significant as they depict many key figures linked to the history and development of both Western Australia and Australia. Political figures who regularly appeared in his cartoon’s included John ‘Happy Jack’ Scaddan, the Premier of Western Australia from 1911 until 1916, and William ‘Billy’ Hughes, the Prime Minister of Australia from 1915 to 1923.

City of Armadale - History House

City of Armadale - History House

Other items by Ben Strange

- CARTOON - THE PREMIERS CONFERENCE BOVRILISED: BUT THE STATES LIVES IN HOPE

- CARTOON - KING COAL'S GROWL

- CARTOON - THE TRIUMPH OF THE CROSS

- CARTOON - EMPIRE PREFERENCE

- CARTOON - ADRIFT - DROPPING THE PILOT

- CARTOON - THE LAW OF THE SUSPECT CALUMNY

- CARTOON - THE GREAT PEACE POSTER

- CARTOON - SHE'S COMING! - THE NEW TERROR

- CARTOON - TWO OF A KIND

- CARTOON - TRANSFUSION OF BLOOD

- CARTOON - STARVATION IN EUROPE

- CARTOON - A LITTLE BABY WITH A BIG BOTTLE

Other items from City of Armadale - History House

Mr. Lovekin in his evidence before the Select Committee on the new Health Bill:- I have generally noticed that whenever there is anything wrong there is revulsion to the eye.

(There is no truth in the rumour that the Government intends to appoint an expert eye-gazer to patrol parks and reserves in search of suspects.)

In this cartoon Ben Strange is playing with Arthur Lovekin’s, the owner and editor of the Daily News, recent statement before a Select Committee into the amendments to the Health Bill, that he could tell by looking into their eyes if someone had a venereal disease.

In response Dr Atkinson, the Commissioner of Public Health, stated “I suppose it is hardly for me to correct any wrong impressions which may have grown up in Mr Lovekin’s mind, but I do not, for instance, think it is always possible to tell a venereal case by simply looking at the patient.”

Ben Strange shows Lovekin staring accusingly at a young demure lady in front of him, while a women with a suggestion of questionable morals stands behind him. The three older ladies on the bench are possibly some of the campaigners for, and against the bill, including Edith Cowan who is featured on the right.

Scan this QR code to open this page on your phone ->