TATTOO APPARATUS

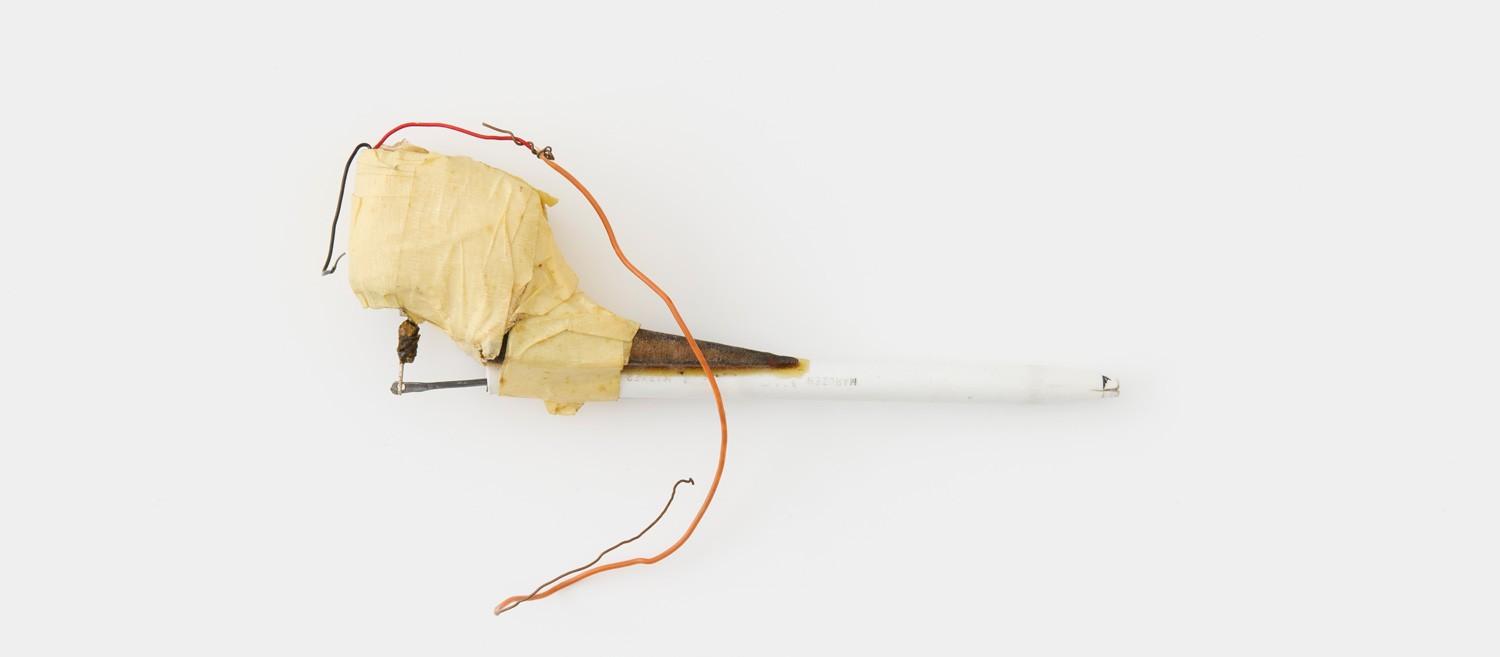

Small, improvised, wood, plastic, metal wire and masking tape tattooing apparatus. Long thin, white plastic, cylindrical pen casing, attached to a wooden rest underneath with wide, yellow masking tape. A small electric motor in a cylindrical metal housing is attached to the end of the wooden rest by masking tape. The entire motor's surface is covered in masking tape. Two unconnected orange electrical wires extend from the bottom of the motor.

This tattooing apparatus was left on site when the Prison closed in 1991, either by a prisoner or after having been confiscated by Prison Officers.

Details

Details

In the early convict system, tattooing was used by custodial authorities as a stigma, to degrade prisoners. There is evidence that convict tattooing was common aboard ships transporting prisoners from the United Kingdom. Such tattooing had the twin purpose of surveillance, as well as to humiliate prisoners as subjects of discipline.

Once arrived in Australia, the cultural shift from the enforced imprint of tattoos, to convicts voluntarily tattooing themselves, was evident from very early on. Traditionally, prison regimes attempted to eradicate the individuality of inmates, relying on uniforms, codes, rules and regulations to transform individuals into conforming prisoners. Realising the potential role of tattooing in defining their sense of identity within prison institutions, inmates took to voluntarily tattooing themselves with words and images to create systems of values and cultural identification.

There are two important differences between ‘professional’ tattoos and ‘prison’ tattoos. Firstly, while professional tattooists appropriately trace designs templates onto the skin, prison tattoos are usually drawn ‘free-hand’. Secondly, since the invention of the first electronic tattoo needle in 1891, most professional tattooists use three to eight tightly bunched non-hypodermic needles which move rapidly up and down on the skin between two to three thousand times per minute. Owing to the necessity for improvisation in prisons to perform what was essentially an illicit activity, prison tattoo application ranged greatly. One example of a more primitive way of applying a prison tattoo is hand-plucking, whereby a sewing or hypodermic needle is repeatedly dipped in ink and stuck on the skin until a line is achieved. These tattoos look more primitive than tattoos created with a machine, because a continuous line is difficult to achieve with a hand-plucked tattoo. Often this form of prison tattoo was self-administered, meaning they were often applied to visible parts of the body, such as the hands or lower arms.

More sophisticated application techniques for prison tattoos usually involved the use of an improvised rotary machine, though unlike professional tattoos, this machine could only be fitted with one needle at a time. The rotary machine was made by the prisoner using a motor taken from something like a cassette recorder, an electric razor or electric toothbrush, which is then connected to a guitar string or sewing needle, which vibrates up and down the barrel of a ball point pen. This form of application appears to be the more common method of tattooing among prison inmates.

The cultural significance of tattooing involves marking members as belonging to the same culture, as much as it involves distinguishing members of one group from another. Prison tattoos were generally regarded by inmates as a way of establishing or re-affirming community, either with those who were left outside, (via tattooed names and pictures of loved ones or gang names for instance), or with those who are inside the prison, or both. Tattooing in prisons is sometimes used as a proto-language. For instance, certain tattoos on the hands and face can denote a specific event or membership in a prison gang.

Open in Google Maps

Nearest geotagged records:

- PHOTOGRAPH OF CATHOLIC CHAPEL AFTER 1988 RIOT (0km away)

- AD REM PRISON NEWSLETTER (0km away)

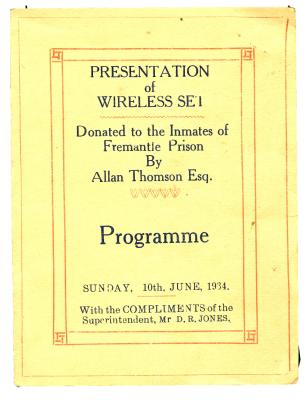

- CONCERT PROGRAMME (0km away)

- IMAGE OF CHRISTMAS FESTIVITIES (0km away)

- ENTRANCE TO FREMANTLE PRISON (0km away)

- IMAGE OF SALLY PORT (0km away)

- IMAGE OF THE MAIN CELL BLOCK (0km away)

- GATEHOUSE/RECEPTION (0km away)

- IMAGE OF BAKING BREAD (0km away)

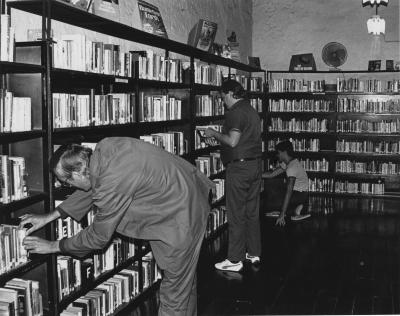

- PHOTOGRAPH OF PRISON LIBRARY (0km away)

Nearby places: View all geotagged records »