An extraordinary tale of survival - 14 days adrift

Aiyana Wright

Zuytdorp Cliffs

Image Credit: Nick Thake

Well, it was perhaps not quite like those little blue and white plastic cooler boxes usually laden with picnic lunches, snags, and an ice-cold beer or two.

This is the amazing story of survival, of Jack Drinan, lost at sea for 14 days in a fishing boat’s icebox.

The Nor 6’s maiden voyage was supposed to be an uneventful journey, to begin what was hopped to be the newly purchased prawn trawlers long and prosperous addition to the Nor West Whaling Company’s current fleet.

For Jack Drinan (38) from Morton Bay, Queensland, it began as many other trips he had skippered during his previous experiences on the East Coast.

However, at 5:20am on April 25th 1963 disaster struck.

Jack was traveling with 3 other crewmen Barry Allen, Ron Pool, and Tony Romanosto. Pool, also from Queensland was at the wheel, Drinan and the others were asleep. With dawn nearly breaking after a long haul through the night, it is believed Pool was drowsy at the wheel, never noticing the dark shape looming on the starboard side.

Drinan was thrown from his wheelhouse bunk with the jolting force of impact, racing onto the deck he knew immediately what had happened. Pool was staggering back from the wheel wide eyed with horror.

‘What happened? What happened’, he cried

Drinan knew exactly what the disastrous crunch and screech of groaning metal against rock meant.

‘MY GOD!’ he shouted, ‘WE’VE HIT THE CLIFFS!’

Here is the story in his own words.

'I heard the props screaming out of the water, then she lurched like a shot bullock, and a huge wave green and cold smashed through the wheelhouse taking me with it. I had one glimpse of white, startled faces. It was the last time I was to see any of them.

'Then I was in black water going down, down. There was a crazy sound of propellers chopping into rocks and I thought: "She's going to come on top of me". But I slid down her side towards the bow, cleared her by some miracle and the next minute was on the rocks. They cut into me like knives and I opened my mouth to cry out, but was pommeled and sucked under by the surf.

'I remember thinking: I'd rather drown than be smashed to death on the rocks, and I kicked myself away from them back into the deep water. This was the first time experience saved my life. I knew all about those cliffs. I knew there was no safety on them - even if a man could gain a temporary refuge on the ledges at their foot, he would be swept off on the next tide. The only hope was floating wreckage and when the brine tank bobbed up in front of me it looked the biggest and most beautiful thing I had ever seen.

‘The brine tanks or ice-boxes on the prawn trawlers are not fastened to the deck, but are seated in wooden rails. Built of bondwood, 8ft by 7ft by 3ft deep and lined with foam plastic they will float until doomsday. I knew, that at least for the moment, I would be safe. Struggling to burst out of my overalls - borrowed overalls much too small - I struck out for its white shape in the darkness as the lights of the Nor 6 turned over and were swallowed by the waves.

'As I dragged myself gasping and exhausted on to the lid of the ice-box, I heard a voice calling "Ahoy there!...."I could still hear that voice calling all the time I was out on the raft. Maybe from the cliff's: I will hear it for the rest of my life.

'Dawn came, the most dismal dawn I have ever seen. I strained my eyes to the cliffs hoping against hope to see tiny figures silhouetted against the skyline. There was nothing but spray and seabirds-and a broken section of the Nor 6's dinghy drifting closer to the shore. Wave scuds broke over the raft and as it increased it distance seawards from the cliffs, I realised that if the wind strengthened I might be washed off.

'Inside the icebox was food, ice, and safety. I had to break through the lid-but how? A twisted iron bar on the outside provided the answer. I wrenched it off and with its sharp end I began to pick at the lid. By noon I could get my hand in and get out some of the ice to chew (my mouth and throat were raw dry with salt) and by dusk I had made a hole big enough to squeeze my body through and had managed to stop up the drain holes in the compartment (one of four in the box) and bail out the sea water. For the moment I was safe, if not exactly comfortable.’

'But I was half crazy with worry -I knew that if the other fellows were on the rocks, rescue boats would have to reach them within 24 hours before their strength failed and they would not be able to hang on any longer. Their lives depended on my being found early enough to alert searchers. But now the wind was strengthening to a half gale, and I was being blown further and further out to sea. About 9p.m. I lost sight of the South Passage lighthouse. I knew that put me at 16 miles out, and the rate of drift was rapidly increasing in the worst possible direction. Out to sea.’

'I knew the search aircraft would be out by next morning. Our own Nor-West Whaling Company had whale spotter aircraft at Carnarvon. But they would be looking up and down the coast for survivors while I drifted out to sea. I must have drifted 50 miles that first night. Curse the wind – it still blew! There was a shark trailing me. A big fellow, about 10 or 12 feet in length and a greenish colour. I think he was a tiger shark but he never came close enough for me to have a really good look

'The icebox floated well. I had no worries about it sinking because it was lined with plastic foam and would float forever. When I had bailed it out it drifted with only three inches submerged bowling along like a big cardboard box on top of the water.

There were 22 oranges and, most valuable of all-nine eggs, some raw meat and sausages, some bacon, a cabbage, and a big tin of dripping which I smeared over my clothes and body to keep the cold out I didn't have much appetite those first days. I was too sick with worry about my companions on the Nor 6 and how my wife and kids would be feeling when we were posted missing. I wondered how long it would be before Jean told them... Jacquelyn (10), Patricia (7), Rosemary (6), and Michael (5)... that would be the hardest part telling the kids'

On Tuesday, April 30th., the pilot of the Nor West Whaling Company aircraft caught a glimpse of something under water along the cliffs. He circled and recognised the shape of the sunken trawler. Police divers were flown north and went down on the wreck in the turbulent water. They identified the Nor and reported that there were no bodies in the wreck...Conditions were very rough, they said. Tracks seen on a beach on Dirk Hartog Island raised hopes momentarily, but police investigating found that they had been made by a station hand.

On May 4th, nine days after being posted missing' newspaper headlines in The West Australian read: HOPE FOR NOR 6 MEN FADES

Jack Drinan still drifting helpless and alone out at sea had long ago lost sight of the land, and he could only guess how far he had drifted.

On the Sunday he had heard the sound of an aircraft far to the east, but it was too distant to see.

'Why did the search aircraft miss me? I had really expected to be picked up within 24 hours. perhaps 48 hours at the outside. But obviously the ice-box floated further and faster than anyone could have expected. I estimated that I was probably 200 miles off-shore by the Sunday when the air search was at its height. None of the searchers thought of the ice-box, and still the wind blew me further out.'

'For four days those damn easterlies blew, and my icebox bucked and dipped further and further out to sea. During this time, I crouched in my compartment like a man in a cave, huddled in misery and despair. At dawn I licked the dew from the icebox woodwork, and felt little hunger. My days were tortured by thoughts of my lost crew-and that voice calling "Ahoy there!" from a cliff cave from which was no escape. - I worried about my family ashore. The shark continued following the icebox.'

'When I emerged blinking in the sunlight of the fifth day to find the ocean blue and calm, I had been travelling at from two to five miles an hour for four days. It is possible I was even further out to sea than my estimate. The sun brought me a return to cheerfulness. I had lived this long. I still had most of my 22 oranges and nine eggs left if the wind backed to the south (and, after all, sou'westers were the prevailing wind at this time of the year) there was no reason why I shouldn't blow right back the way I'd come.'

"I set to work to solve my two principal problems-to control the drift of the raft, and to provide Some way of getting ashore once it was within reasonable distance of land. "If I only had a sail or rudder", I thought. I looked at my empty raft and thought again "Why not?" I asked myself. With the iron bar and the ice-shovel-standard equipment in all prawn boats - I started to hack and chip at the lid, to sweat and strain at the bolts. At the same time I started on what I called my "dinghy"."

"Since I couldn't paddle the icebox itself because it was far too big. I reasoned I would have to cut a section of the lid - shaped roughly like a surf ski- for the last stretch to the shore. Here luck was with me again for the icebox was built of marine bondwood and lined with aquaplas (a plastic foam) which floats 60lb deadweight to every square foot of its bulk. They were ideal materials for my purpose.

In a surprisingly short time I had a narrow section ready to try out. Paddles were improvised and trembling with excitement I launched it while the icebox raft bobbed benignly in the sunshine of the calm ocean. I regret to say this first effort was a complete and utter failure.

"The section was too narrow. It capsized continually. I just couldn't control it. I climbed back on the icebox and began to cut a bigger section. Chip, chip, chip with the shovel blade. It was a slow process 'The new ski took much longer to make but it was a better effort. When it was completed, I looked at it with satisfaction. I was certain it would do the job. Now for navigating the icebox. Sails presented no problem. In the icebox were a number of bondwood slats used for dividing it up into prawn compartments. Jammed with bits of stick, so they caught the wind, and made fine sails.

"The ninth day was a black one for me, on the water, and Jean ashore. Out on the icebox raft I saw lights approaching in the night. I rubbed my eyes, then jumped up yelling with delight - it was a tanker. I thought it was heading straight for me! But it passed by 200 yards away without stopping.

It was so close I could hear the rumble of propellers, see the cabin lights, and the chart-room on the bridge. But none of the men on that snug warm ship saw me weeping and waving on my raft. I shouted until I felt my lungs would burst. The tanker rumbled on into the night unknowing.

I used to carve my diary in the woodwork on the icebox. At first I used a bit of metal strip, but it kept breaking. Then I got the wooden screw and that was pretty good. Before I set off on this my first attempt to reach land on the ski. I carved this message and it should be still on the raft if it is ever found

Steep Point Cliffs

Image Credit: Emma Craig

THIS BRINE TANK SUPPORTED J.DRINAN AS A LIFE RAFT FOR TEN DAYS FOLLOWING THE WRECK OF THE VESSEL NOR 6... AT 4PM ON THE TENTH DAY I SET OUT FOR SHORE ON A RAFT MADE FROM THE LID. MAY GOD HAVE MERCY ON MY SOUL.

'I decided to chance my luck and leave the ice-box, to try to reach land on the raft or ski, taking with me two eggs and an orange in holes I had dug under the seat. It could have been a fatal decision. But once again luck was on my side.

'I kept looking back at the icebox as I was not very confident. After a short distance I was amazed to see a storm bearing down from the seaward side. It was just what I had waited so long for. I made it back to the icebox just as the wind started in earnest from the south west. When it started to rain it was an exciting moment. It came down in torrents and it was no problem to drink out of cupped hands.

I had been licking the dew off the icebox lid and drinking small amounts of sea water, and trying to make the oranges and eggs last as long as possible. I used to swim nearly every day and this helped slow down the dehydration!

I had scratched 13 marks on the icebox and crossed one off every day. There was no rational reason why I thought it was a critical number. But when the 13th day dawned and there was no land I became very despondent. I said to Our Lady of Fatima, Lady you've let me down! 'But the sou'west was blowing hard, the icebox was almost surfing on giant swells and at last

I was travelling the right direction. 'On the 14th day I woke, and there it was. Land, big, brown and beautiful. I knew then that I was going to make it.

Looking toward the land Drinan caught sight of a lighthouse, counting the flashes with some shock, he realised he had drifted back to where he had started from. Knowing if he didn’t act now before the conditions changed, he would lose his chance of surviving. Loading his pitiful provisions aboard his roughhewn raft Drinan paddled hard, away from what was his salvation, toward the land unsure if he would make it.

Paddling all night he finally rounded Steep Point and Monkey Rock familiar landmarks beckoning him to known safety. Drinan made his way to the lighthouse and was unable to find provisions. In a desperate attempt to find food and help, Drinan decided to attempt the relatively safe crossing to Dirk Hartog Island on his raft.

South Passage between Steep Point and Dirk Hartog Island

Image Credit: Nick Thake

'Halfway across I heard the sound of diesel motors. I looked around over my shoulder and saw the crayfish freezer boat ‘Sonoma’ bearing down on me. At first, they thought I was a tourist on a surf ski’

There followed one of the more dramatic radio reports in recent Western Australian maritime history. One of the crew was giving a routine radio report confirming Sonoma's safe arrival in South Passage. Suddenly he interrupted his broadcast.

"Hang on a minute!"

There was a silence and the sound of the handset being put down with the usual statics and crackles. Then the operator resumed with a new excited note in his voice. 'Hey!' There's a bloke here on a raft!. He says he's from the Nor 6!" When Jack got on board the first thing he saw in the Sonoma's wheelhouse was a statue of Our Lady of Fatima.

‘I went down on my knees and thanked her for my deliverance.’

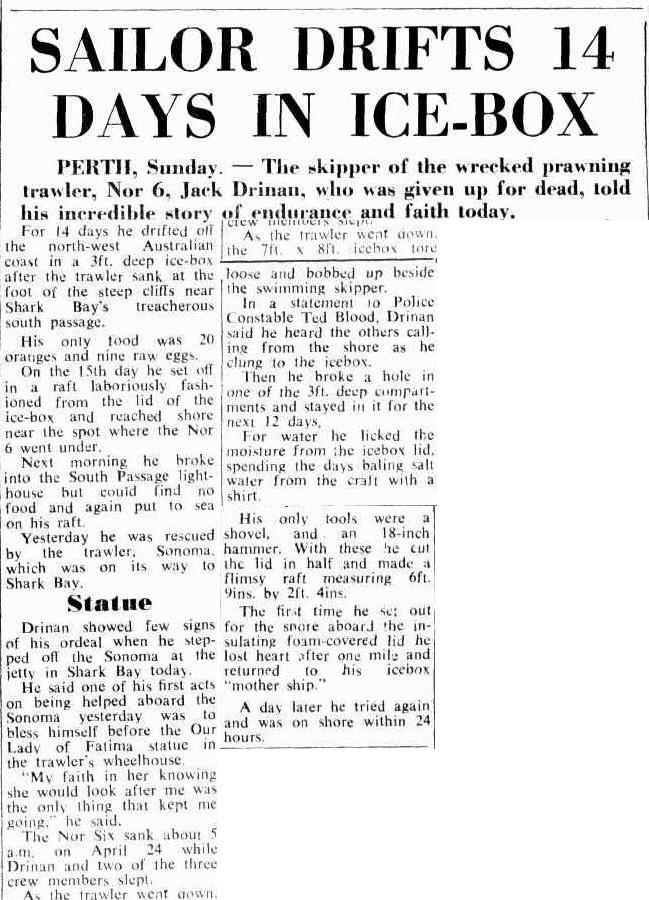

The news was a sensation, on front pages all around Australia. Then came the hard questions How had Drinan managed to survive 14 days at sea? Where was this brine tank he talked about? What had really happened to the Nor 6?

Articles from Trove - National Library Australia

In 1963 Hugh Edwards was a young journalist with the Perth Daily News.

‘I first heard the seemingly-miraculous story of Jack Drinan's survival over the car radio driving back from diving on the Gilt Dragon wreck at Ledge Point. When I reached home there was an urgent message to ring my editor.

'Pack your bags, son' Stuart Joynt said 'And get to Carnarvon as quick as you can. Find out whether this fellow's the genuine article or whether there's more to it all than meets the eye. There was a pause and I could imagine him taking a puff on one of the cigarettes which seemed permanently in place under his neatly-trimmed grey moustache. 'Either way' he concluded, exhaling the smoke. 'It's a good story!'

Carnarvon was 800 kilometres drive, and I had plenty of time to think on the way up with photographer Dave Tanner. I was prepared for either of the eventualities the editor had suggested. As he said, whether it was the real thing or an elaborate hoax, it would still be a good story.

It took only a few minutes with Jack Drinan to convince me that he was sincere. His hands shook, he cried easily, he was a man who had been through a dreadful time. Though it was clear that the loss of the Nor 6 was an unfortunate accident he felt a savage guilt about the loss of his crew. Even though it was a steerman's human error he was the skipper. He found it especially hard to forgive himself for being the only survivor.

"Why not one of the others?' he asked, and the question was addressed not to me but to himself. The story did not come out easily, but I never doubted his sincerity. The resultant newspaper articles filled a full page of the Daily News every day for five days. The words in the stories were Jack Drinan's, exactly as he spoke them to me. I hardly had to alter a line. The account in this book (Shark Bay: Through Four Centuries 1616 to 2000 by Hugh Edwards) is Jack's too, just the way he told it all to me 26 years ago, passed on again to the reader.

As I left Carnarvon, he shook my hand and apologised for his shaky condition. Then he looked me in the eye and said ‘The icebox will prove it one day.’

'The ice-box?'

'Yes' he said 'One day it will prove me right. One day it will turn up some place, somewhere and it will be just as I told you. The evidence, if you like. Then you'll know I told the truth." I told him that I didn't need the icebox to convince me. He thanked me and I never saw him again.

Jack, after a long and successful sea going career, died in Perth of cancer aged 61 in the 1980's never knowing that shortly after, during Cyclone Herbie in 1988, the icebox was washed ashore on the Bellefin Prong proving Drinan’s unbelievable story.

The icebox was eventually collected and is held by the Shire of Shark Bay.

The icebox Jack survived 12 days adrift in

The stone cairn erected in the Edel Land National Park (4WD access only) is a beautiful memorial to Barry Allen, Ron Pool, and Tony Romanosto.

It is a place to stand on the stark and rugged cliffs, and gaze out into the capricious majesty that is the Indian Ocean, wondering at the ability of one human able to survive in such a savage and endless waters.

Stone cairn, in memory of Barry Allen, Ron Pool, and Tony Romanosto

Excerpts taken from the book Shark Bay: Through Four Centuries 1616 to 2000 by Hugh Edwards