World War 1 photographers fell into two main categories: amateur and official. Reflecting the astonishing naivety about the war and presumably its anticipated brevity, Australian soldiers were each given a Vest Pocket Kodak on the voyage to Egypt to document their exploits. The cameras were quickly confiscated when the adventure spiralled into a bloodbath.

Australia accredited only three official war photographers: Herbert Baldwin in 1916, a British photographer, who lasted barely six months before being discharged due to ill health (a common euphemism for “shell shock”) and Australian photographers, Frank Hurley and Hubert Wilkins.

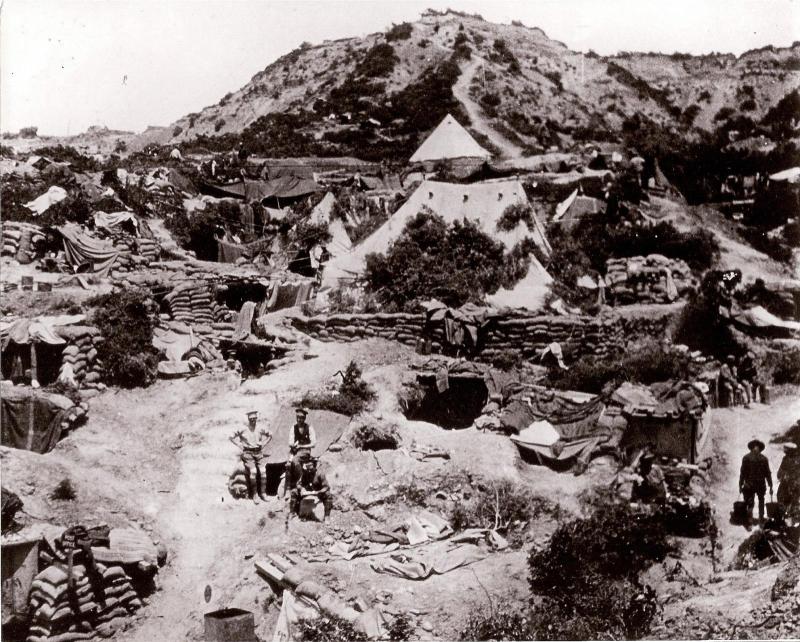

Though both Hurley and Wilkins produced an outstanding body of work, photos of Australians in combat never appeared in newspapers during the war. Published photographs were restricted to staged images of soldiers on training exercises, soldiers as tourists in Egypt, departing for, or arriving at various destinations, or portraits of the young men who died accompanied by captions including mandatory references to heroes, sacrifice, the fallen, the defence of freedom and Empire. In contrast, it was the unpublished photographs, which provide a vivid tableau of unseen military life. Some captured the enormity of the battle, the nightmarish conditions, the bleak and ravaged landscape, and the Australian dead, dying, maimed and emotionally fragile.

https://theconversation.com/we-censor-war-photography-in-australia-mores-the-pity-40816

In spite of an official ban of private photography at the Front, the Australian Army Museum of WA has an extensive collection of images from the beaches and trenches of Gallipoli from 25 April 1915 until evacuation in December. Small pocket cameras of several designs were marketed to departing soldiers who were anxious to record their great adventure. The contrast between official and amateur photographs as discussed in the article in The Conversation noted above is clearly shown in this sub-collection.